Part of my Kyrgyzstan travel stories, this journey moves through nomadic culture and open landscapes, in a country where movement has long been a way of life.

Not the Welcome I Imagined

Researching about Uzbekistan, I realized it wasn’t only part of the Silk Road, but also part of a trio of countries often visited together: Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Kazakhstan.

Of course, I wanted to see them all.

For purely logistical reasons, Bishkek became the starting point of my journey.

From there, my journey followed a full loop around Issyk-Kul — one of the largest alpine lakes in the world.

We left straight from the airport toward Cholpon-Ata, a tourist city by the lake.

It was my first time traveling with this travel agency, and the very first thing I heard from the guide upon arrival was:

“The hotel they booked for you is closed.”

What?!

I was traveling alone, and for a moment, I felt uneasy.

The entire place looked deserted — Issyk-Kul is a summer destination, and the season was already over.

After a while, they sent us to another hotel.

Well… kind of.

It was an old building, just as empty as the previous one. Ironing boards and baby cribs lined the wide, questionably tasteful corridor leading to the rooms.

Inside, an old tube TV waited for me. It felt as if I had entered a time machine instead of boarding a regular flight.

I called the agency and quickly realized that everything around was closed. Arguing would get me nowhere.

So I decided to step outside, breathe, and leave that unexpected journey into the past for later.

Unfolding the Patchwork Quilt

More than natural beauties — mountains, emerald-green rivers, and reddish landscapes that look like Mars — what I really wanted to see were the traces of old civilizations.

So many peoples passed through these lands that it’s hard to keep track of them all. This region feels like a patchwork quilt, where each piece represents a different culture that once lived here.

I was eager to unfold that quilt and look at its details more closely.

As the sun was almost gone, we arrived at another open field, where massive stone slabs covered in rock art were scattered across the landscape, dating from 2000 BC to the 9th century AD.

Alongside the carvings, another striking presence: the Balbals — stone funerary statues associated with ancient Turkic cultures, dating from the 6th to the 10th centuries AD.

They could be shorter or taller than me, and somehow they all seemed to share the same cute expression. It’s hard to believe they were funerary monuments at all.

Footnotes from Elsewhere

Balbals are ancient stone statues found across Central Asia, especially in Kyrgyzstan.

Created by Turkic nomadic cultures between the 6th and 10th centuries, their meaning is still debated.Some scholars believe they represent enemies defeated in battle, symbolically condemned to serve the warrior in the afterlife. Others suggest they may depict ancestors, spirits, or ritual figures, acting as guardians of memory rather than trophies of war.

Just a few steps from one another, they felt like proof of the richness of a place where different civilizations occupied the same spaces over time.

It felt like a fast-forward History class — happening right there, on the spot.

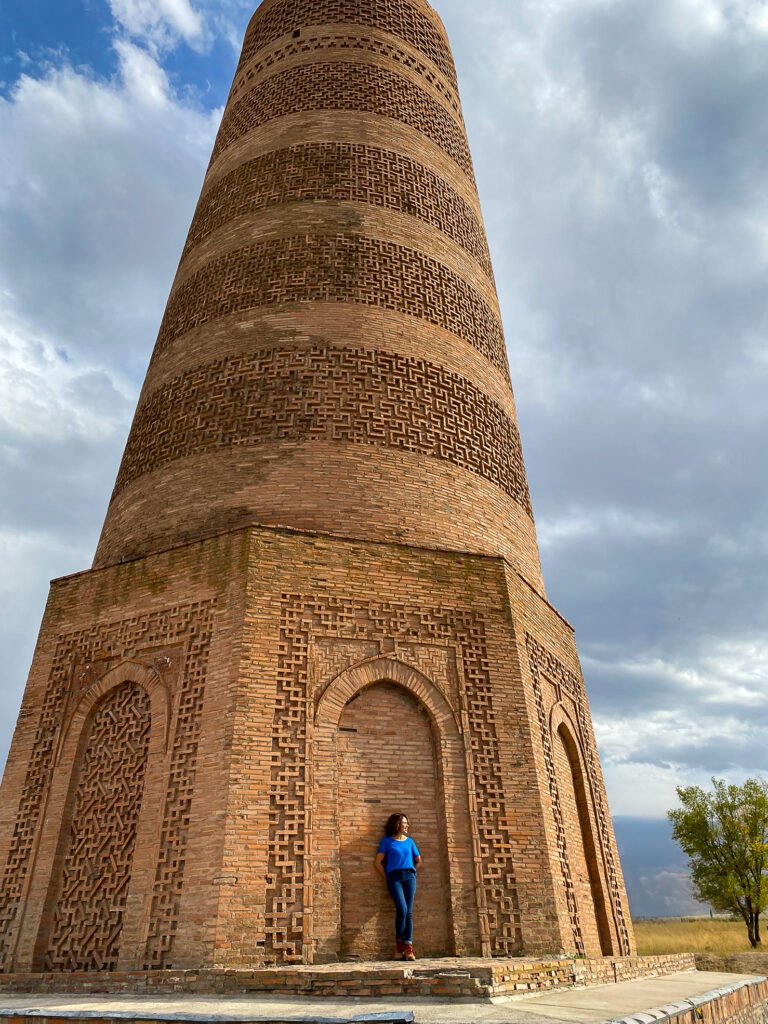

Another piece of this quilt appears at the Burana Tower, an 11th-century minaret standing lonely in a wide, open field.

It is one of the few remaining traces of Balasagun, once an important commercial center along the Silk Road.

And it was time to hit the road, toward landscapes shaped — and often hidden — almost entirely by mountains.

It was a perfect blue-sky day when we stopped in a valley surrounded by mountains, their slopes covered with pine trees. The bucolic scene was completed by a river cutting through the land with its emerald-green water.

The silence was suddenly broken by a group of men herding cattle.

Watching them, I had the impression that the scene wasn’t very different from that of their ancestors — Turkic nomadic peoples who once moved through these same valleys.

Here and there, dome-shaped tents — yurts — appeared in the landscape. During the summer, families move with their herds to high-altitude pastures, turning yurts into their homes for weeks, sometimes even months.

Footnotes from Elsewhere

Yurts are traditional portable dwellings used by Central Asian nomadic peoples.Designed to be assembled and dismantled quickly, they reflect a way of life shaped by movement, seasonal pastures, and a deep connection to the land — a tradition that remains part of everyday life in Kyrgyzstan.

Some yurts were assembled in the Jety Oguz Gorge, famous for its reddish rock formations. The most iconic one is the Seven Red Bulls, and not by chance — they dominate the wide canyon, almost as if the aligned bulls were guarding the area from their strategic position.

Even more intense in color is the Skazka Canyon, also known as Fairytale Canyon. To be honest, I didn’t see much of a fairytale there — but I saw plenty of Mars.

It felt like my second trip to the Red Planet without leaving Earth. The first was in Wadi Rum; now, Skazka.

Walking among its sharp shapes and deep red tones made me feel as if I were on another planet, where the contrast with the blue sky and the lake turned the entire landscape into a theatrical scene.

Urban Layers

Leaving the silence of the nomadic landscape behind, we made our way to Karakol and its Russian heritage.

Here, Kyrgyzstan didn’t feel nomadic at all. Instead, it revealed something entirely new to me: the Dungans — a community of Chinese Muslim origin.

Just imagine a mosque that looks like a Chinese temple. Yes, it exists — and it’s in Karakol.

Footnotes from Elsewhere

Founded in the late 19th century as a Russian military outpost, Karakol grew into one of Kyrgyzstan’s most ethnically diverse cities.Over time, it became home to Kyrgyz nomads, Russian settlers, and communities of Dungans and Uighurs who arrived after fleeing persecution in China.

The Holy Trinity Cathedral, an Orthodox church built entirely of wood following Russian traditions, stands as another layer of this complexity. Against its brown walls, green rooftops and onion-shaped domes rise quietly above the city.

Although Islam is the predominant religion in Kyrgyzstan, religious practice tends to be moderate and deeply influenced by pre-Islamic traditions — something that becomes visible in the coexistence of mosques, Orthodox churches, and everyday rituals.

Contrasting with everything I had seen so far was Bishkek.

Here, the Soviet period is still very much alive: buildings aligned in straight lines, heavy gray facades, military monuments, bronze statues. The whole composition felt like an oversized headquarters.

What Nomadism Tastes Like

One place, however, immediately caught my attention: the Osh Bazaar.

Its aisles filled with colorful, aromatic products were a pause for all the senses — taste included, as I left carrying bags full of fresh treats.

On my way out, something else caught my attention: a round bread, shaped like a shallow bowl — lepeshka.

What drew my eye were the intricate patterns stamped on each one, making every loaf look slightly different.

I love bread, and I’ve tried many unforgettable ones along the way. But this wasn’t only about taste.

It was, without a doubt, the most beautiful bread I had ever seen.

And I can’t finish this post without mentioning one last experience. Kyrgyz cuisine reflects its nomadic past, and most meals I tried revolved around meat and rice or pasta, often swimming in so much broth that they were almost soups.

The detail is the meat: mainly lamb — and horse.

I tried it.

It has a strong flavor, unlike anything else I had tasted. I didn’t love it, and I didn’t hate it. It just felt unfamiliar. I suspect I would need more time to get used to it — and something tells me I eventually would.

I could see how intense the Kyrgyz relationship with horses is, rooted in centuries of nomadic herding.

What I didn’t expect was how far it extended — all the way to the table. I was genuinely surprised to find an entire section of the market dedicated to horse meat.

And staying on that subject, there’s also kymyz — fermented mare’s milk.

This one, I decided to take on faith alone. I had heard far too many stories of people trying it fresh and spending days locked inside a restroom. I still wanted to make it to Uzbekistan.

Pingback: Uzbekistan Travel Stories | Notes From Elsewhere